Somali refugee women in Thailand find solace in art therapy

10 August 2017|Oratip Nimkannon, Psychosocial counsellor, JRS Thailand

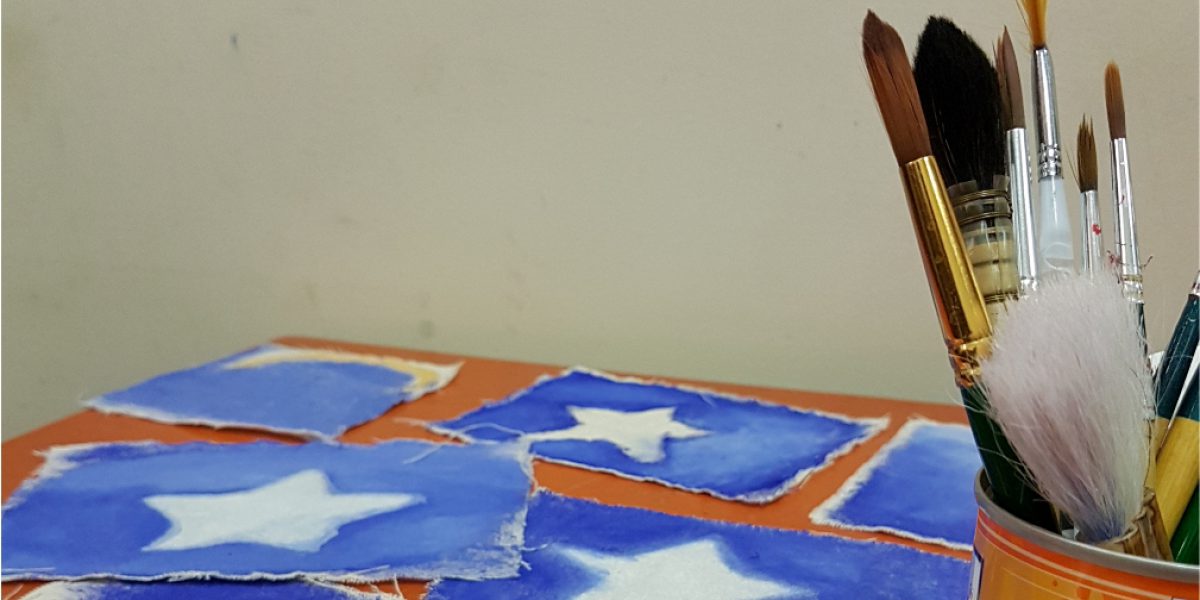

Bangkok, 10 August 2017 — Six women in colourful hijabs sit in a brightly-lit room, quietly dipping paintbrushes into pots of blue, yellow and black poster paint. One young woman, Nala*, 25, glances down at her work— the outline of a skinny dark stick figure sketched onto white fabric — and a faint smile stretches across her face.

“This is my daughter,” she tells the other women, who fall silent as they study the painting. It is the first time that Nala, whose child was left behind in Somalia when she fled to Bangkok nearly 2.5 years ago, has spoken about her past or her family.

The 3-month support group, run by Jesuit Refugee Service’s registered art therapist Oratip Nimkannon with the Urban Refugee Program, has brought the women together for art therapy sessions launched earlier this year to help asylum seekers process loss while creating a sense of community and friendship.

Although the first few sessions provoked anxiety in many of the women, who suffer from unresolved trauma stemming from Somalia’s brutal 30-year civil war, as the support group sessions unfolded, the women began to paint and speak more openly about the lives they had left behind and their uncertainties about the future.

“I don’t know where my next home will be,” said Aaden*, 18, who has been waiting for resettlement to a third country for two years. Aaden’s painting depicted a single-storey house with a small door and windows — a sharp contrast to the towering and overcrowded apartment building she now shares with hundreds of other low-income families.

The process for refugee status determination can take up to six years in Thailand, where dozens of Somali asylum seekers have sought refuge from a protracted conflict that has sent more than one million people fleeing across international borders since 1991, according to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). Even for those recognized by UNHCR to be refugees, the future is uncertain as resettlement possibilities dwindle and local integration is unavailable.

Since Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohammed was ushered into power in February 2017, he has officially declared the country a ‘war zone’ and sworn to eradicate Al-Shabab and other warring militants from the fragile state on the Horn of Africa.

The refugees are both victims and survivors of three decades of state instability — and their vulnerability shows itself in their artwork.

In an earlier art therapy session, 19-year-old young woman, Khaadija*, asked if she could paint a tumultuous black sky. Reserved and soft-spoken, those who know Khaadija said she often looks sad and seems to have a lot on her mind.

“Surviving years of civil war and inter-clan conflict has affected many of the women’s abilities to trust and feel safe in the world,” explained Nimkannon, a registered art therapist with the Australian and New Zealand Arts Therapy Association.

According to World Psychiatric Association (WPA), art therapy is a potent tool to help individuals reconstruct their interpretation of daily reality and process traumatic emotional material.

Art is both “a clue to the inner structure of the brain… [and] a means of potential transformation”, notes the WPA.

Psychiatrists also stress that displaced individuals feel bereavement from the loss of cultural norms, religious customs and social support that accompanies migration. Without help, the compounding stresses increase their risks of mental illness, reports a study co-authored by Dinesh Bhugra, a mental health professor at King’s College based in London.

In Somalia, where clan relations and complex kinship structures dominate collective social life, the absence of loved ones can be particularly devastating.

“Social connection is an important but missing element in the lives of many young Somali women seeking asylum in Bangkok,” said Nimkannon, who says the safe space provided by art therapy aids psychological healing.

Painting images of home, as popular Somali songs peal in the background, the women’s comfortable chatter seems worlds away than that of the bloodshed and inter-clan violence now taking place on Somali soil, where roughly half a million people have died since the country descended into chaos thirty years ago.

“The women have found support in each other’s company, learned to voice their needs and trust the therapist as well as each other,” said Nimkannon.

“Though the sessions are not enough to create long-lasting change, the women have been given back some sense of control over their lives.”

*Names have been changed to protect identity.

The program is funded with a State Department grant from the Bureau of Population Refugees, and Migration.