Cambodia: Displaced women forced into marriage deserve an apology

24 May 2013|Dana MacLean

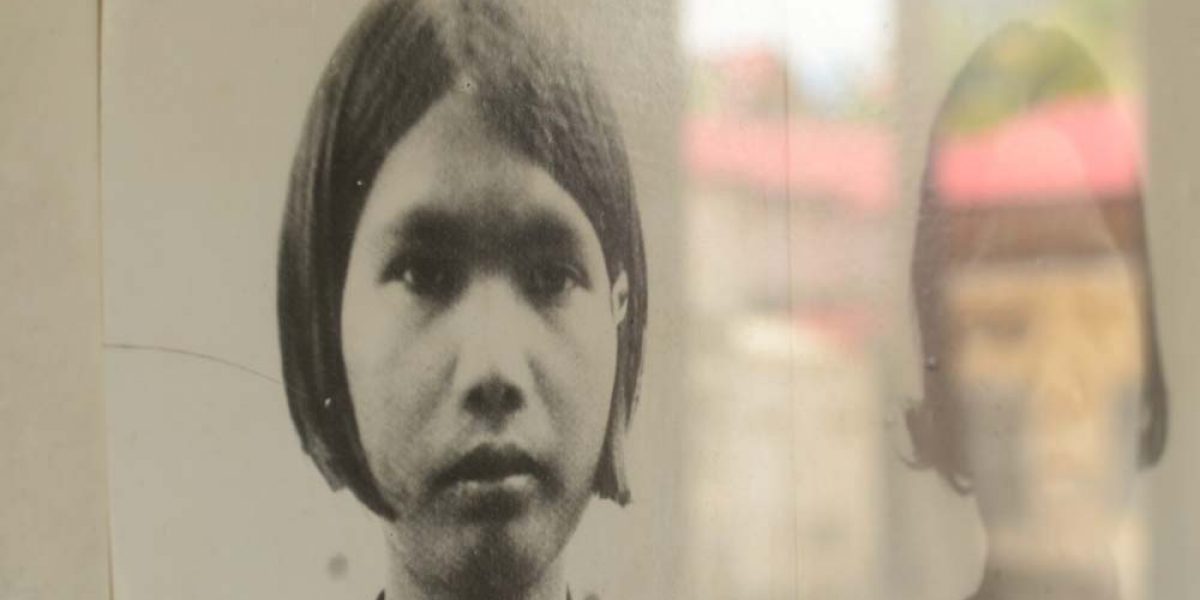

Phnom Penh, 24 May 2013—Cambodian women who were displaced by the Khmer Rouge and forced to marry strangers between 1975 and 1979, are taking their cases to the ECCC courts in Phnom Penh as a way to heal.

“Our clients want to know why people were forced to marry, understanding the reasons would help them [make sense of what has] happened to them,” said Ms Beini Ye, a lawyer representing the Civil Parties in the ECCC and program advisor on sexual and gender based violence to the Cambodia Defenders Project, a local NGO providing legal aid to victims of the Khmer Rouge.

While the total number of women displaced and forced to marry is currently unknown, coerced marriage was common in all regions throughout Cambodia under the genocidal regime which wiped out nearly two million and forcibly relocated urban residents en masse to the countryside to farm in cooperatives.

“The use of forced marriage in particular was systematic and widespread, employed by the regime to secure loyalty to the Government by breaking family bonds and taking [the] major life decision [of] who to marry out of the hands of citizens and entrusting it to the State,” said Ms Zainab Hawa Bangura, the special representative to the UN Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, in a statement issued on 1 March 2013.

Sexual and gender-based violence is often used by repressive armed forces as a tool of war in order to destroy the social fabric of a community and degrade its members, according to campaigns such as Stop Rape in Conflictand the UN Women’s initiative, Stop Rape Now. While new developments in Cambodia’s court system are a step forward for women survivors, inefficiency of the system and impunity for SGBV remains an ongoing problem in Cambodian society, say rights groups.

Legal recognition may take baby steps

The ECCC decided in February 2013 that the current ongoing case against the Khmer Rouge officials could be severed into mini-trials, giving sexual violence and forced marriage the potential to be tried in current ongoing cases against former Khmer rouge officials. Unfortunately, in April 2013 the Trial Chamber decided not to include forced marriage in the current trials, but hope still remains for victims and their lawyers that it will be allowed in the third sub-trial.

This would be an important step for acknowledging that rape and other forms of sexual abuse when perpetrated by armed forces in conflict situations, are crimes against humanity, according to JRS.

“Victims of abuse often feel the need for public recognition that what was done to them was wrong, in order to move forward and re-build their lives,” said Ms. Junita Calder, the advocacy spokesperson for JRS Asia Pacific.

In other war-torn countries, such as Rwanda (where up to 250,000 women were raped within three months during the 1994 genocide), or Yugoslavia (where roughly 60,000 women were raped from 1992-1995 ), legal decisions defining rape as a war crime have been put in place through the International Criminal Tribunals, according to the UN, wherein rape is outlined as a war crime and a crime against humanity.

But often times the issue of rape is still sidelined by legal systems and silenced by stigmatization, going unpunished and perpetuating a cycle of acceptance in communities.

“Sexual violence is the only crime against humanity that is routinely dismissed as ‘collateral damage’,” said Nancee Bright, the chief of staff to the UN special representative on sexual violence in conflict, in a statement issued in December 2011.

“We are not very optimistic that forced marriage will ever be brought up at the ECCC,” said Ms Ye, referring to the lack of certainty in the courts about whether third sub-trials featuring forced marriage would even take place.

Post-conflict recovery hindered by corruption

From 2000-2005 the UN Security Council issued five resolutions condemning sexual violence, recognizing that even when conflicts end, sexual violence often continues to afflict societies because the denial of human rights has been normalized and strong family units do not exist to protect and support women.

In Cambodia, it is still uncertain if the women survivors’ voices will ever even make it to trial.

“The court has split the case into small sub-trials dealing with forced. Whether future sub-trials, including the charges of forced marriage, will ever take place is very uncertain given the age of the accused and the decline of funding,” said Ms. Ye.

Survivors of any type of SGBV in Cambodia are unable to access real justice due to “criminal justice system failures” and corrupt settlements made out of court, in which police and law enforcement officials take a cut, according to Amnesty International’s 2011 and 2010 reports.

But without proper address, women will have a difficult time moving forward.

“There is a feeling of justice that comes with a judgment by a court,” explained Ms. Ye.

Whether trials are conducted through traditional courts, such as those seen with the Gacaca trials in Rwanda, where more than 1.9 million cases were managed by over 12,000 village ‘courts’, or in international court systems, such as the prosecution of three Bosnian Serbian commanders convicted of rape as a war crime in the UN for acts committed during the war in 1992, what women deserve is to have a space where their voices can be heard, say the UN and NGOs.

Even if the ECCC decides not to undertake the GBV claims against former officials, the survivors’ lawyers have established a platform for truth telling and documentation to ensure that the survivors’ voices are heard. It can be accessed here: http://gbvkr.org/

“All people have the human right to stand as individuals before the law and have their voices heard,” stated Ms. Calder.

Dana MacLean, JRS Asia Pacific Communications Officer