Australia: Continuing to serve across continents

13 July 2011|Catherine Marshall

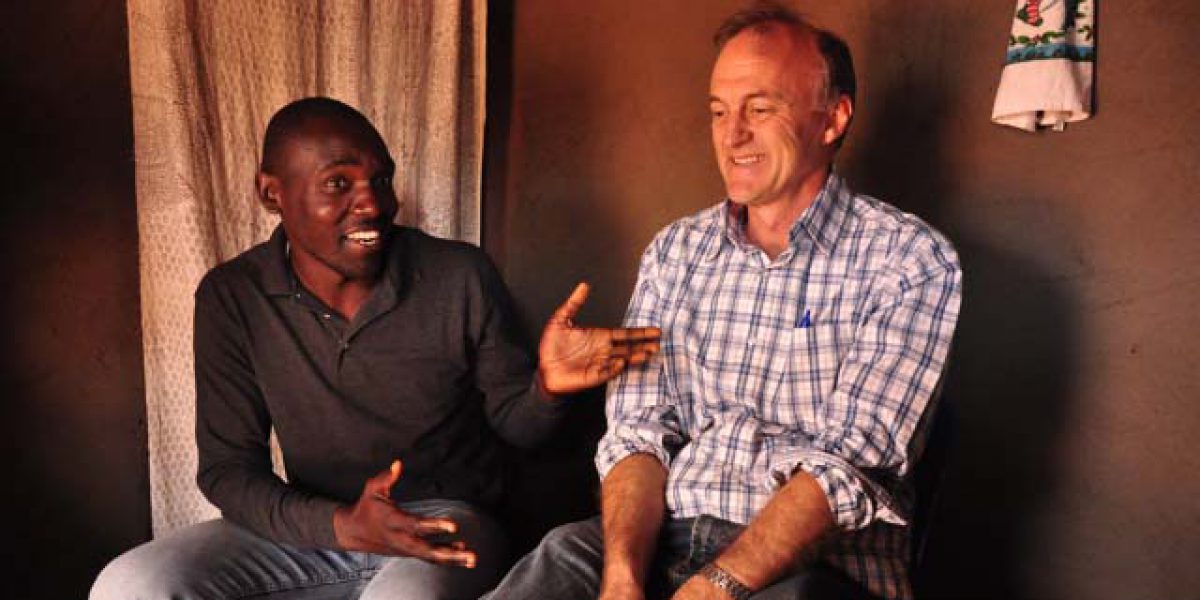

Sydney, 13 July 2011 – It’s a long way from inner-city Sydney to the vast countryside of sub-Saharan Africa, but Australian Jesuit David Holdcroft – whose work Jesuit Mission is privileged to support – has made the journey with apparent ease.

One year into his appointment as Regional Director of Jesuit Refugee Service Southern Africa, David has gone from working with a small group of refugees seeking asylum in Australia to managing humanitarian projects across five countries: South Africa, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In his new role David finds himself spending his days with some of the very people who hope to call Australia home one day, a position of trust in which he is able to draw heavily on years spent working as the Director of JRS Australia in the organisation’s Kings Cross offices.

The divide between refugee issues in Australia and those in Africa is broad: Australia accepts just over 13,000 refugees each year, whilst South Africa has absorbed into its towns and cities hundreds of thousands of undocumented migrants from across Africa. Most of these migrants come across the border from Zimbabwe, a politically troubled country which has seen a massive outflow of people in recent years. And with the support of Jesuit Mission, JRS Southern Africa is now implementing a unique program at the source, in the hope that Zimbabwean schoolchildren at risk of fleeing can be persuaded to make a life in their homeland instead.

“Nearly all of the people moving to South Africa are young, and they’re going because their families are starving”, says David. “Some are orphans and so in a sense they don’t have a reason to stay in Zimbabwe. We’ve identified a population there amongst the school kids who we think are at risk of moving to South Africa, and we’re supporting the schools and the students so that they can be self-sufficient. Sometimes they’re by themselves; sometimes they’re staying with relatives or are looking after siblings.”

New challenges

Understanding this link between the subsistence and migration has enabled JRS to tailor its programs more effectively.

“We went in [to Zimbabwe] to help starving people, and incidentally these were the same people who were migrating. The poverty is very deep. The program then evolved over time – I think it’s is a very handy program to have.”

Whilst about three million Zimbabweans are estimated to be living outside of the country, another 100,000 people have been internally displaced. Many of them were uprooted as a result of government policy or farm invasions by the political elite. They experience multiple “evictions”.

“There’s a whole rural transient population”, says David. “Many of those people are third or fourth generation immigrants from Malawi or Mozambique and they haven’t necessarily got citizenship so they’re basically stateless, which is part of the problem. They don’t have a great purchase in the political process and can find it difficult to get documentation, which is the first step in securing accommodation.”

JRS works in an area where about 400 such families are at risk of being dislodged yet again, because the tract of land on which they live has been zoned for medium density housing development.

“The people who are living there now are squatters and the Jesuits were trying to get them a benevolent result. We’ve proposed a pilot project to move the families off this land and settle them elsewhere, to get them into schools and employment.”

On the other side of the border, JRS works with the thousands of Zimbabweans who have streamed into South Africa, providing emergency food, clothing, accommodation and other assistance. In Johannesburg and Pretoria they offer vocational education, facilitate the enrolment of young refugees in schools, help refugees to set up their own businesses or identify creative employment opportunities for these people, many of whom speak fluent French.

“We’ve worked with South African Airways in the hope of providing them with French-speaking flight attendants,” says David. “Unfortunately the human resources department vetoed the idea because Congolese refugees wouldn’t be able to return to their homeland on flights to that country – according to refugee law, refugees can’t go back to their own country.”

But hiccups such as this haven’t deterred David from implementing modern solutions to an age-old problem.

“Despite the big variations [in our works] what I really want to do is develop a more cohesive framework for JRS. Different projects have grown up in different places, and I want to get an overarching vision so that we can work more as a region.”

By all accounts, JRS is already on the right track: last year the organisation helped 7,000 people in the Gauteng office, a number which blows out to 25,000-plus when the indirect beneficiaries such as partners and children are taken into account.

“What is really encouraging in South Africa is the consistent feedback I get that JRS has been helpful, that it has credibility and is tightly-managed”, says David.