Research and Advocacy for Climate Policy and Action (RACPA)- The plight of coastal communities amid climate and environmental change.

29 September 2023

Salatiga is in Central Java, Indonesia, around an hour’s drive from Semarang. It is the base of The Institute for Social Research, Democracy, and Social Justice (Percik), JRSAP’s partner to implement the Caritas Australia-funded Research and Advocacy for Climate Policy and Action (RACPA) project in Indonesia, one of two project countries, along with the Philippines.

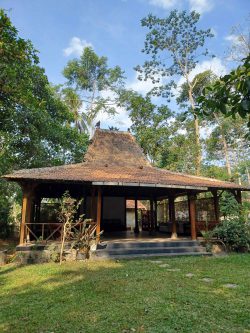

Percik’s offices in Kampung Percik are in buildings that have been relocated to preserve them from demolition, and rebuilt here, floor, walls, roof and all. With RACPA, the question that needs answer is what will happen when individuals, households and communities must relocate, or be relocated, because of climate and environmental change? How can an entire village be rebuilt, along with its social, economic and cultural fabric, from the ground up?

Rising tides, falling earnings

A fishing village in Tambakrejo in Semarang Regency could help provide answers. The villagers were displaced by the “normalization” project that aimed to dredge built-up sediment in the East Flood Canal to reduce the impact of flooding. Initially, the community was left to fend for themselves: staying with relatives, seeking shelter in makeshift homes beneath a bridge. Eventually, with the help of civil society groups, they secured assistance from the government, which relocated them not far from the original settlement. Free housing was provided for 97 households, but only for a period of five years. Already, two years have elapsed since then.

Every year, usually from December to March, the sea level rises more than a meter, flooding the village. The fishermen face changes in the seawater’s behavior. When the tides rise, they avoid going out to fish or simply stay near the coast, as it is too dangerous. At such times, they lose even the 100,000 Rupiah (around 6 dollars) to make on average each day.

The villagers have tried to reduce the impact of the banjir rob, tidal flooding, by planting mangroves, but the designation of the area for industrial use means the mangroves could be removed at any time, as has already happened to some seedlings they planted. The villagers trace the worsening of the annual tidal flooding to the building of a new settlement in another area, Tanah Mas. This is why it is important for people living on the coast to work with those living in other, especially higher, areas to address the problem.

From planting rice to planting fish

In a different perspective, the residents of Wonoagung in Demak Regency welcome the river normalization project. They see it as necessary to address the problem of annual flooding faced by their village, which used to be a farming community, but had to convert their paddies to fishponds. From past to present, the community must adapt from planting rice, to “planting fish.” Because of the frequent flooding they experienced with seawater, which increased the soil’s salinity and made it less suitable for farming. They adapted, converting the paddies in the western part of the village into fish-ponds They cultivated milkfish as well as shrimp, which fetched good prices, enabling them to weather the financial crisis in the late 1990s. Back then, they made enough that they could meet their needs and still have fish left in the ponds for others to enjoy, free.

Unfortunately, the harvest failed as their shrimp stock was affected by a fungal disease linked to polluted waters. Later, global shrimp prices declined as well, prompting them to adapt yet again, importing a new shrimp variety from the United States—vannamei or Whiteleg—in the hope of better returns. It has been three years since they made the shift, and they are hoping the conditions will recover.

Meanwhile, flooding continues to plague the village, and it seems to be getting worse. Every year, around December to February, the community finds itself inundated. The water rises up to 40 centimeters (about 1.31 ft) in a house. The fish and shrimp escape from the fishponds, and the water brings skin diseases. Children find it hard to go to school since roads are flooded, even though the school itself is built on higher ground.

The wrong season

Elsewhere in Central Java, some communities are in even direr straints. One of the villagers from Wonoagung was originally from Bedono, where some fishermen had to make space inside their houses for their boats, preventing them from being carried away by the tides.

It is believed rising sea levels linked to climate change are a contributor to the flooding. Globally, climate change and extreme weather events threaten the lives and homes of about 216 million people, according to a World Bank report. But the people we speak to from Wonoagung do not mention ‘climate change.’ Instead, they have their own term: ‘salah mongso.’ The wrong season. To help them deal with the flooding from the wrong season, the villagers wonder if the government should raise the river embankment, removing mangroves in the process.

The support of Caritas Australia and our project partners is vital in addressing this and other questions affecting the plight of coastal communities amid climate and environmental change. As Pope Francis noted in Laudato Si’, a quarter of the world’s population lives on or near the coast and stand to be affected seriously by rising sea levels. Caring for our common home means helping them adapt in the face of this challenge.