Asia Pacific: The Rohingya: Between the devil and the deep blue sea

11 April 2011|Chris Lewa, Director of the Arakan Project, an NGO dedicated to research-based advocacy on the Rohingya, writes about the persecution and rejection facing this oppressed minority of Burma.

Bangkok, 11 Aril, 2011 – In January 2009, the Rohingya hit international media headlines when the world saw images of hundreds of emaciated boat people being rescued off the Andaman Islands of India and in Aceh, Indonesia. They had been intercepted in Thai waters, transferred to deserted islands, tortured and eventually cast adrift by the Thai military on the high seas, in boats without engines and with little food and water. At least 1000 people were dumped at sea in three separate incidents. Hundreds were reported missing.

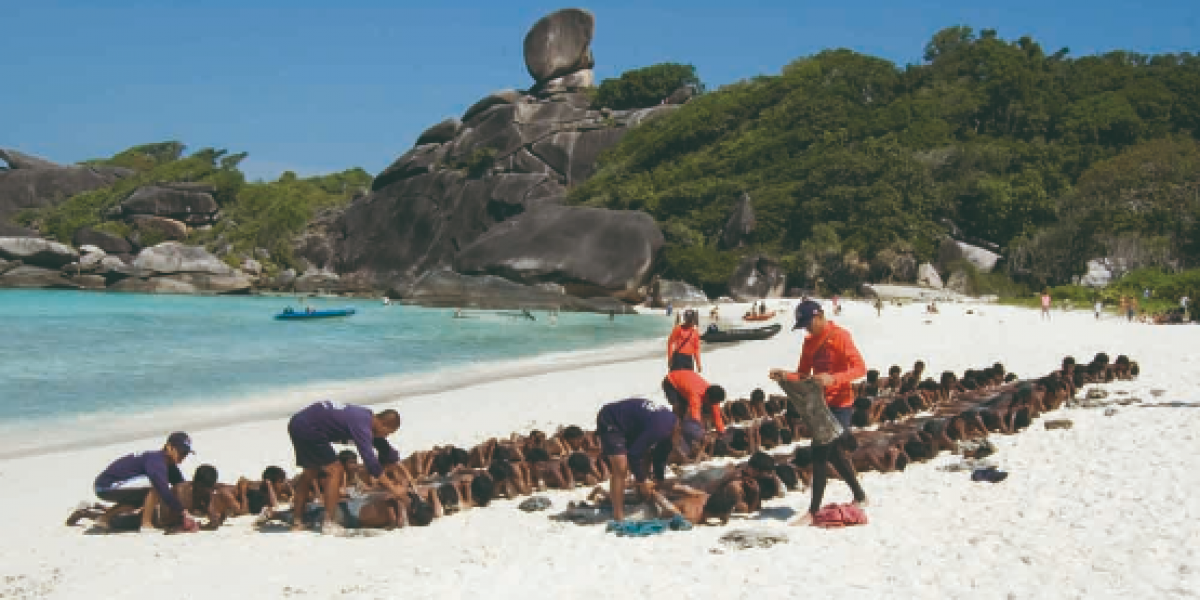

Sharif, an unregistered Rohingya refugee, was rescued in Indonesia after surviving two push-backs. He left Bangladesh on a rickety boat, together with 92 others, and after days lost at sea, landed on the Similan Archipelago of Thailand, a diving paradise for tourists, on 23 December 2008. “Foreigners were swimming around,” he recalls. “Some came to us in a speedboat and gave us food and water. Then the Thai Navy arrived and ordered us to lie face down on the beach, hitting us in front of the tourists. The next day, they transferred us to an island with a barbed wire enclosure. Five more boatloads arrived and our number rose to 580. I was detained for nine or ten days, during which Thai soldiers beat us every day.”

“The Thai Army forced us to board four boats from which the engines had been removed. In my boat, in which 83 people were crammed, there was only a sack of rice, three buckets of water, a plastic sheet and two bamboos. They towed us out for a night and a day and cut the tow rope. We drifted for three days and encountered a storm. Our boat was about to sink when a fishing trawler saw and rescued us. Brought back to Thailand, we were again handed over to the army and taken back to the same island. Again we were beaten mercilessly. Two more boatloads arrived. Suddenly, they put all 198 of us on a large barge and once again towed us for a night and a day before cutting the rope. This time, we drifted for 12 days. One man died of dehydration and starvation and the rest of us were barely alive. On the thirteenth day, Indonesian fishermen found us and brought us ashore.”

Exclusion

The Rohingya rank among the world’s most persecuted minorities. They number about 725,000 and mainly inhabit the three townships of North Arakan in Burma, flanking the border with Bangladesh. Muslim and of South Asian descent, they are related to the Chittagonian Bengali across the border and are distinct from the majority population of Burma, who are of Southeast Asian origin and mostly Buddhist.

Especially since the military takeover in 1962, the Rohingya have faced exclusion in Burma. The 1982 Citizenship Law, which confers the right to nationality on 135 ‘national races’ listed by the government, makes no mention of the Rohingya, rendering them stateless. Denial of citizenship is the key mechanism of exclusion, institutionalising discrimination and arbitrary treatment. The Rohingya are strictly confined to North Arakan. Couples must obtain official permission to marry and sign a pledge not to have more than two children. They face arbitrary arrest, extortion, forced labour, confiscation of land. The compounded impact of these and other abuses undermines the economic survival of the Rohingya: a deliberate policy of the military regime to prompt their departure. For the Rohingya, leaving Burma is always a one-way journey because the authorities will not re-admit them.

Exodus

Hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas have fled Burma. Impoverished Bangladesh has already witnessed two mass influxes, of 250,000 refugees each time, in 1978 and in 1991/92; both were followed by forced repatriation. Today, 28,000 remain in two precarious refugee camps, assisted by UNHCR and a few NGOs. Meanwhile the exodus continues from Burma and some 200,000 Rohingyas try to eke out a hand-to-mouth existence in Bangladesh, vulnerable to exploitation and arrest. In 2009, Bangladesh launched a crackdown on unregistered Rohingyas and more than 2,000 were pushed back across the border. The drive intensified in early 2010 and thousands are flocking for safety to a makeshift settlement sprawled around Kutupalong refugee camp.

Others move on: since 2006, 10,000 have sailed on overcrowded boats to reach Malaysia via Thailand, as Sharif tried to do. The suffering of Sharif did not end in Indonesia, after he was rescued, for he was detained in a government compound in Idi Rayeuk. Managing to escape, he was smuggled to Malaysia in September 2009, where we met him on a construction site. The other boat people detained in Indonesia were finally released on 17 December 2009 and settled temporarily in Medan.

Detained

Not so for many others. One year on, Rohingya boat people are still languishing in a dark and crowded hall in the immigration detention centre in Bangkok, worried about their family’s survival back home and wondering whether they will ever be released. Among them is Saber, a 35-year-old widower from Buthidaung Township. He left his three daughters, aged ten, six and four, back in Burma. A poor farm labourer, Saber lost his wife three years ago in childbirth. “I took her to Buthidaung hospital and the doctor said she needed a blood transfusion. But a bag of blood costs 20,000 Kyat (circa 2.2 euro) which I couldn’t afford. She was severely anaemic because I couldn’t give her proper food.”

Left alone, Saber had to look after his girls, work for his family’s survival and fulfil the forced labour duties imposed by the authorities. Unable to cope, he applied for permission to marry again but was refused as widowers must wait three years before they can remarry. This is why Saber decided to leave Burma after selling his small house to pay for the journey and leaving his daughters in the care of his brother.

On 3 January 2009, Saber embarked on a flimsy boat. The inexperienced boatman lost his way and the engine broke down. Saber and his companions were starving when they encountered the Burmese Navy. “I was severely beaten by Burmese Navy men; the scars are still visible. My toes and the lower parts of my legs are still numb,” he explains. “They also set fire to a cloth with kerosene and seriously burnt two of us.” Finally, the boat ended up in Thai waters.

Embarrassed internationally by the push-backs earlier in the month, the Thai government did not push these boat people back; on 27 January 2009, 78 were brought ashore by the Thai Navy and provided with medical care in a media parade. But later, away from the television cameras, the Rohingyas were incarcerated in Ranong immigration detention centre, in conditions so appalling that two survivors, including a 15-year-old, died in custody. Transferred to a centre in Bangkok, they risk indefinite detention because the authorities have so far not allowed UNHCR to determine their status.

Rejected

Their history of persecution in Burma undoubtedly qualifies the Rohingya for protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention. But none of the concerned countries in the region has ratified the Convention or enacted domestic legislation to protect refugees. Only Malaysia allows UNHCR to screen Rohingya asylum seekers. Governments are reluctant to offer protection within their borders for fear of creating a pull factor. Instead, they sometimes describe the Rohingya influx as ‘economic migration’ and implement deterrence schemes to prevent access to their territories: protracted detention, push-backs, crackdowns and denial of access to refugee protection. Calls for a regional solution are merely a tactic to diffuse individual states’ responsibility to protect members of this beleaguered minority.

Meanwhile, the Rohingya continue to face unimaginable suffering. In Thailand and India, the detained survivors of the horrific sea voyages just over a year ago, mirror their people’s plight. Saber was desperate when he learnt that his brother could no longer afford to look after his daughters. In tears, he told us: “It hurts me so much to hear that my daughters are now beggars. Why are we detained? I have not committed any crime. I only wanted to escape from the hellish life of misery in Burma.”